I generally look forward to visiting the permanent collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art because it’s like visiting an old friend-- familiar and inspiring. There are certain pieces I always reacquaint myself with at the PMA, namely Eugene Carriére’s Young Girl Counting, Whistler’s Nocturne, VanGogh’s Rain, Peter Doig’s Figure in a Mountain Landscape II (no longer on view) and the Cy Twombly room. These pieces ground me and inspire me in my own paintings. But what I also look forward to when I visit the museum is a possible new reaction to a work, or several works, I have passed by during previous visits. Depending on what I am working on in the studio, a piece in the collection may have more relevance to me in my own artistic endeavors…a piece that may have seemed insignificant during previous viewings.

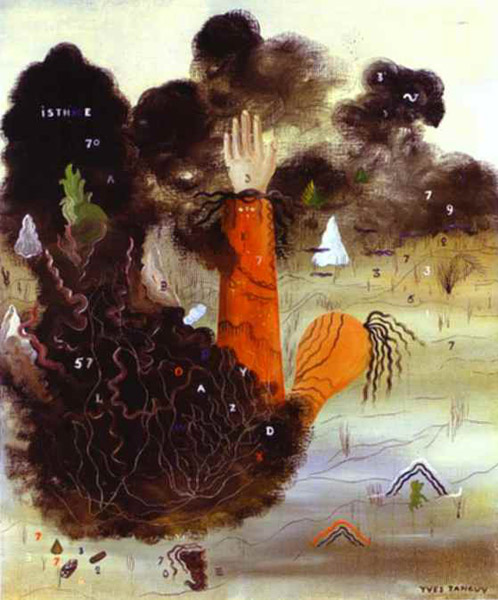

On Sunday’s visit to the PMA, this piece was Yves Tanguy’s The Storm (Black Landscape). I’m sure I’ve passed by this painting on several other occasions. It is located in the Modern wing, in the hall, with a grouping of a few other Surrealist paintings. Let it be known, that I don’t have much love for Dali’s work or other typical Surrealist paintings which contain shadows without color in them, dripping objects, pseudo-sexual imagery and simplified amoeba-esque objects that are supposed to represent figures. The subconscious, dreams, Freud... I get it, I get it. But this piece by Tanguy stood out to me, with its quick brushwork and honest attempt to depict an other-worldly “landscape”. Maybe more aptly called a dreamscape.

|

| Yves Tanguy, "Storm (Black Landscape)", 1926, oil on canvas |

Tanguy’s Storm could be a blown-up detail of a Hieronymous Bosch painting, with its confined space devoid of fresh air, limited palette and its freakish un-human figures. It resembles some sort of terrarium in which organisms are cultivated and observed. There is certainly some influence of Chinese ink paintings here in Tanguy’s use of calligraphic line, coupled with a Miro-like way of describing a world without gravity. But what’s really quite interesting is that Tanguy was essentially a self-taught painter, which might explain his refreshing early take on Surrealism. The use of gestural line and brushwork in these pieces stands out against the typical over-blended, smoothed out structure-less, cold Surrealist 'scapes. Tanguy paints a world that could exist deep beneath the sea, chock full of Chihuly-esque seaforms, or high above us in an entirely different weightless universe. But I see a world which reveals a psychological space, a moment, a feeling- one which many Surrealists were after. It is a space that is claustrophobic and neurotic while remaining whimsical and light, despite its heavy black ground.

I’d also like to suggest that although this painting was done early in his career, it exemplifies a period of Tanguy's work which could be described as his “golden period”. Many artists have what we sometimes refer to as a “golden period”- a period of production characterized by both incredible quantity and quality. Van Gogh’s paintings during the last few years of his life and Charles Burchfield’s golden year of 1917 are just two such examples of periods of intense creativity, and effortless flowing of ideas and solid work. The more I looked at paintings by Tanguy done during the time that Storm was completed, the more I realized that the years 1926-27 may have been somewhat of a “golden period” for him. The paintings of this period reveal a pure idiosyncratic vision and aesthetic competency. His later works I’m not as convinced by, or at least, they do not have the purity that Storm and others of the same time period exhibit.

|

| Untitled, 1926, oil on canvas |

|

| The Hand in the Clouds, 1927, oil on canvas |

|

| Extinction of Useless Lights, 1927, oil on canvas |